Ächärya Sthulibhadra

The kingdom of Magadha, in the state of Bihar, possessed a long and rich history. During Mahävir’s time it was ruled by King Shrenik of the Shishunäg dynasty. This dynasty ended with the death of Shrenik’s

great grandson Udayi. Magadha then passed into the hands of the Nanda dynasty, where Dhanänand succeeded nine generations of his family’s rule. This was around 300 BC or about 200 years after Lord Mahävir’s nirvana.

Dhanänand was far from being a just and noble ruler as he was very greedy. He had heard a legend about some hidden treasure that belonged to one of his predecessors and was desperate to get his hands on it. Unfortunately, he had no idea where this treasure was hidden. However, he knew that his old Prime Minister Shaktäl, who had served his father, had knowledge of the treasure’s whereabouts. Dhanänand

tried everything he could to locate the treasure, but Shaktäl refused to provide any information about the whereabouts of this treasure. The king then forced him to retire and the administration was entrusted to the other ministers.

Shaktäl was a wise, knowledgeable, and highly respected person in the kingdom. Many scholars and high ranking officials admired him and were eager to consult him on important matters. However, they avoided communicating with him because they feared that the king would not approve of this.

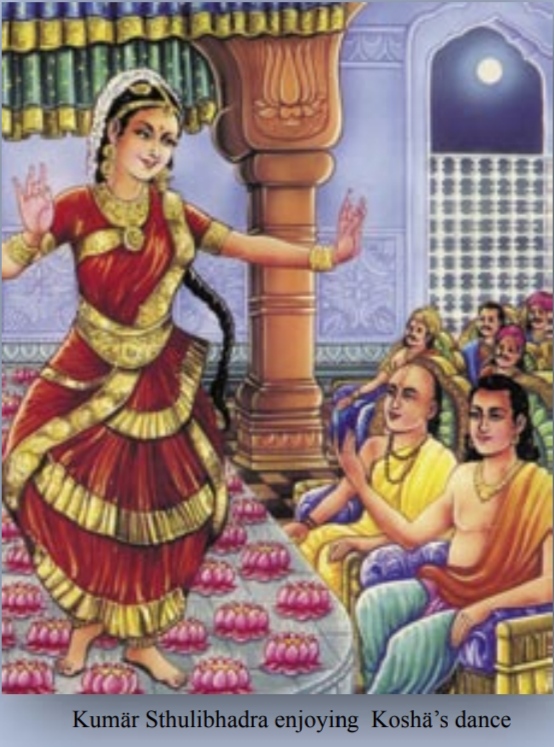

Shaktäl had seven daughters and two sons, Sthulibhadra and Shriyäk. Sthulibhadra was smart, brilliant, and handsome, but not very ambitious. In Patliputra, the capital city of Magadha, there lived a beautiful young dancer named Koshä. From a very young age, Sthulibhadra would watch her perform. They fell in love with each other. His family disapproved of the relationship. However, Sthulibhadra was deeply in love. He left home at the young age of 18 and started living with Koshä. He was infatuated with Koshä and abandoned all interest in his career and other family members. King Dhanänand intended to appoint him to a high position in the court but Sthulibhadra declined the offer. The king therefore appointed his younger brother, Shriyäk, to the position.

Kumar Sthulibhadra enjoying Koshas Dance.

As time passed, things began to look grim for Dhanänand’s reign. The citizens of Magadha witnessed major political upheavals and turmoil. People felt dissatisfied with the current regime and looked for the end of the Nanda dynasty. King Dhanänand felt insecure and was suspicious of all his

ministers and advisors including Shriyäk and his father Shaktäl. Shaktäl also knew that the king was very suspicious of him. Hence, he was worried about the political future of his younger son.

Shaktäl decided to sacrifice his life in order to provide proof of Shriyäk’s loyalty to the king. He requested his son, Shriyäk, to kill him in the presence of the king and other ministers. This way the king would have proof that Shriyäk was a very loyal minister. He explained to Shriyäk, that prior to the execution he would swallow some poison. This way Shriyäk would not truly (morally and religiously) be responsible for his father’s death. And the king would feel that Shriyäk was very loyal to him because he killed his own father. Thus, Shaktäl arranged to die at the hands of his own son in order to prove his son’s loyalty.

When Sthulibhadra learned about that tragic event, he was taken aback. By that time, he had spent 12 years with Koshä and had never cared for anyone else. His father’s death was an eye opener. He started reflecting on his past. “Twelve long years of my youthful life! What did I get during this long period?” He realized that he had not acquired anything that would endure. The tragic end of his father brought home the reality that all life comes to an end. “Is there no way to escape death?” He asked himself, “What is the nature of life after all? Who am I and what is my mission in life?”

Delving deep into these questions, he realized that the body and all worldly aspects are transitory, and physical pleasures do not lead to lasting happiness. He looked at his image in the mirror and noticed the unmistakable marks of a lustful life. He also realized that he was wasting his youth. He decided to search for lasting happiness. He left Koshä and went straight to Ächärya Sambhutivijay who was the sixth successor to Lord Mahävir. Surrendering himself to the Ächärya, he said that he was sick of his lustful lifestyle and wanted to do something worthwhile with his life. Here was a young man of thirty who seemed to have lost the vigor of youth. The lustful life he had led had taken a toll on his body; but the brightness inherited from his illustrious father still glowed on his face. Seeing Sthulibhadra’s determined and humble state, the learned Ächärya saw in him a great future for the religious order and accepted him as his pupil.

Sthulibhadra did not lose much time to adjust to the new pattern of his life. The ambition that he had missed in his youth emerged in the man. He was keen to make up for lost years and devoted all his energy to spiritual upliftment. He worked diligently and in no time gained the confidence of his guru. His life as a monk was exemplary. He had successfully overcome his senses of attachment and lustfulness, and gained control over his inner enemies. It was time for his faith to be tested.

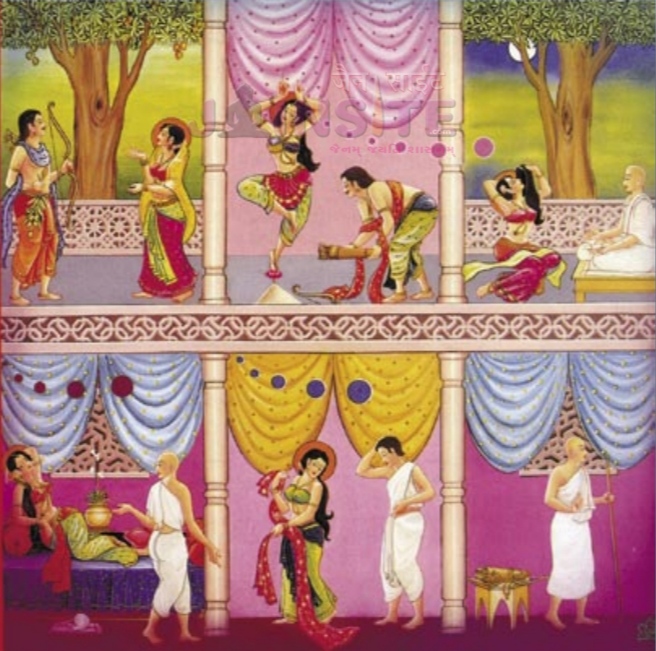

The monsoon season was approaching and the monks had to settle in one place during the rainy season.Sthulibhadra and three other monks (Sädhus) who had attained a high level of equanimity wanted to test their faith and determination by spending the monsoon time (4 months as per Indian climate) under the most adverse conditions. Each one chose the most adverse conditions for themselves. One of them requested permission from his Ächärya to stay at the entrance of a lion’s den; another wanted to spend the time near a snake’s hole; the third wanted to spend the 4 months on top of an open well. The Ächärya knew that they were capable of withstanding these hardships and permitted them. Sthulibhadra humbly requested that he would like to spend the monsoon in the picture gallery of the residence of Koshä. The Ächärya knew how difficult this test would be for Sthulibhadra. However, the Ächärya also knew Sthulibhadra’s determination and felt that spiritually he would not progress any further without passing this test. Therefore, he permitted Sthulibhadra to spend the monsoon at Koshä’s house.

Sthulibhadra approached Koshä and asked her permission to stay in the picture gallery during the monsoon season. Koshä was surprised to see him. He had left her in such an ambivalent state that she had not been sure if she would ever see him again. She was missing him and was happy to see him again. However she did not know the true purpose of his return. They both had their goals for the monsoon season. Koshä endeavored to win him back into her life. She used all her seductive skills and felt that having him live in her picture gallery was to her advantage. Sthulibhadra’s goal was to overcome the strong temptation of Koshä’s beauty. Who would win? Sthulibhadra’s strong faith and determination served him well during this test. He focused his mind on spiritual meditation. He spent his time meditating on the transitory nature of life and the need to break away from the cycle of birth and death. Ultimately, Koshä realized the wastefulness of her life and became his disciple. Sthulibhadra emerged spiritually stronger from this experience.

Sthulibhadra approached Koshä

At the end of the monsoon, all the monks returned and described their experience. The first three monks described their success and they were congratulated. When Sthulibhadra reported the success of his test, the Ächärya rose from his seat in all praise and hailed Sthulibhadra for performing a formidable task. The other monks became jealous. Why was Sthulibhadra’s feat so much more impressive than theirs? After all, they had endured physical hardships while he had spent the monsoon in comfort and security. The Ächärya explained that it was an impossible feat for anyone else. The first monk boasted that he could easily accomplish the same task the following monsoon. The Ächärya tried to dissuade him from his intent because it was beyond his capability. The monk wanting to prove his spiritual strength to the Ächärya, persisted and was reluctantly given permission for the next monsoon season.

The next monsoon the monk went to Koshä’s place. The immodest pictures in the gallery were enough to excite him. When he saw glamorous Koshä, his remaining resistance melted away and he begged for her love. After seeing the pious life of Sthulibhadra, Koshä had learned the value of an ascetic life. In order to teach the monk a lesson, she agreed to love him only if he gave her a diamond-studded garment from Nepal, a town 250 miles north of Patliputra. The monk was so infatuated that he left immediately for Nepal, forgetting that monks were not supposed to travel during the monsoon. With considerable difficulty, he procured the garment and returned to Patliputra confident of receiving Koshä’s love. Koshä accepted the beautiful garment, wiped her feet on it and threw it away in the trash. He was stunned. He asked her, “Are you crazy, Koshä? Why are you throwing away the precious gift that I have brought for you with so much difficulty?” Koshä replied, ‘Why are you throwing away the precious life of monkhood that you have acquired with so much effort?’ The humbled monk realized his foolishness and returned to his Ächärya to report on his miserable failure. There was immense respect for Sthulibhadra from that day onwards.

Sthulibhadra played a major role in later years to preserve the oldest Jain scriptures known as the twelve Anga Ägams and the fourteen Purvas. Jain history indicates that Ächärya Bhadrabähu was the last monk who had complete knowledge of all the Jain scriptures. Ächärya Bhadrabähu succeeded Ächärya Sambhutivijay as head of the religious order. Both Ächärya Sambhutivijay and Ächärya Bhadrabähu were the disciples of Ächärya Yashobhadra.

In those days, the Jain scriptures were memorized and passed on orally from guru to disciple. They were not documented in any form. Under the leadership of Ächärya Bhadrabähu, Sthulibhadra thoroughly studied eleven of the twelve Anga Ägams.

An extended famine prevented Sthulibhadra from studying the twelfth Anga Ägam known as Drashtiväda, containing the fourteen Purvas. During the famine Ächärya Bhadrabähu-swämi migrated south with 12,000 disciples. Ächärya Sthulibhadra succeeded him as the leader of the monks who stayed behind in Pataliputra. The hardships of the famine made it difficult for the monks to observe their code of conduct properly. In addition, many of the monks’ memories failed them and many parts of the Anga Ägams were

forgotten.

The famine lasted for twelve years. After the famine, Sthulibhadra decided to recompile the Jain scriptures. A convention was held in Patliputra under the leadership of Sthulibhadra. Eleven of the

twelve Anga Ägams were orally recompiled at the convention. None of the monks at the convention could remember the twelfth Anga Ägam and its 14 Purvas. Only Ächärya Bhadrabähu swämi had this knowledge but he had left southern India and was now in the mountains of Nepal to practice a special penance and meditation. The Jain Sangha requested Sthulibhadra and some other learned monks to go to Ächärya Bhadrabähu-swämi and learn the twelfth Ägam. Several monks undertook this long journey but only Sthulibhadra reached Nepal. He began to learn the twelfth Anga Ägam and its 14 Purvas under Ächärya Bhadrabähu.

Once Sthulibhadra’s sisters who were nuns, decided to visit him in Nepal. At this time, Sthulibhadra had completed 10 of the 14 Purvas. He wanted to impress them with the miraculous power he had acquired from learning the 10 Purvas and knowledge from the twelfth Ägam. He transformed his body into a lion. When his sisters entered the cave, they found a lion instead of their brother. Fearful of what may have happened to him they went directly to Bhadrabähu-swämi. Ächärya Bhadrabähu realized what had happened and asked the sisters to go back to the cave again. This time Sthulibhadra had resumed his original form and the sisters were joyful to see him alive and well.

However, Bhadrabähu-swämi was disappointed that Sthulibhadra had misused his special power for such a trivial purpose. He felt that Sthulibhadra was not mature enough in his spiritual progress and therefore refused to teach him the remaining four Purvas. A chastised Sthulibhadra tried to persuade him to reconsider but Bhadrabähu-swämi was firm. It was only when the Jain Sangha requested Ächärya Bhadrabähu to reconsider his decision that Sthulibhadra was allowed to learn the remaining four Purvas. But Ächärya Bhadrabähu attached two conditions for Sthulibhadra:

• He would not teach Sthulibhadra the meaning of the last four Purvas

• Sthulibhadra could not teach these four Purvas to any other monk

Sthulibhadra agreed and learned the remaining four Purvas. Since Jain scriptures were not written down and Ächärya Sthulibhadra had made significant effort to save them after the famine, his name stands very high in the history of Jainism. Even today, his name is recited next to Lord Mahävir and Gautam-swämi by the Shvetämbar tradition.