Parasnath bhagwan story in english

Homage to Sri Parsvanatha, Protector, Supreme Spirit, tree for the support of the creeper of all the auspicious* occasions (kalyana). Now the very purifying life of Parsvanatha is celebrated for the benefit of the whole world and for my own benefit.

In this zone, named Bharata, of this same Jambudvipa, there is a city Potanapura like a new piece of heaven. The ornament of the earth, a habitation for meetings with Sri, it is frequented by kings, like the lotus-bed of a river by hansas. Rich men there shone like younger brothers of Srida because of their wealth and like full brothers of a wishing-tree because of their great generosity. It was magnificent beyond the sphere of words from its resemblance to Amaravati; or rather, Amaravati was magnificent because of a resemblance to it. Its king was named Aravinda, bee to the lotus-feet of the Arhat, the abode of Sri, like the ocean. Just as he was unique among the powerful, so he was among the discerning. Just as he was chief of the wealthy, so he was of the glorious. Just as he divided money among the poor, protectorless, and unfortunate people, so he divided day and night among the aims of existence. Corresponding to the king, there was a Brahman, a family-priest, an advanced layman, who knew the Principles soul, non-soul, et-cetera, named Visvabhuti. He had two sons, Kamatha and Marubhuti, older and younger, borne by Anuddhara. Varuna was the name of Kamatha’s wife and Vasundhara of Marubhuti’s, endowed with beaugrace. Both (the sons) had learned the arts and both were competent in the acquisition of property, affectionate towards each other, a source of joy to their parents. Recalling the formula of homage to the Pancaparamesthins*, engaged in concentrated meditation*, Visvabhuti died and became a chief god in Saudharma. His wife, Anuddhara, worn out by fever because of separation from him, her body dried up by sorrow and penance, died, engaged in the formula of homage.

The brothers performed the funeral rites of their parents and in course of time, enlightened by Rsis Hariscandra, became free from sorrow. Kamatha remained there, always occupied with domestic affairs. When the father has died, generally the elder son is the head of the house. Marubhuti, always knowing the worthlessness of worldly existence, became averse to sense-objects, like an ascetic to food.* Devoted to precepts of undertaking study and fasting, engaged in concentrated meditation, he passed days and nights in the fasting-house. Having desisted from everything objectionable, Marubhuti’s idea was always, “I shall wander near a guru.”

Intoxicated by the wine of negligence, always confused by wrong-belief, Kamatha on the other hand became devoted to other men’s wives and gambling without restraint. Vasundhara, Marubhuti’s wife, with fresh youth became the causer of delusion to people, like a living poisonous creeper. But she was never touched at all by Marubhuti, an ascetic by nature, even in sleep, like a desert creeper by water. Then she, desirous of sense-objects and not having any union with her husband, considers her youth like a jasmineB in a forest. Kamatha, who was naturally lustful, undiscerning. after seeing his sister-in-law again and again, addressed her affectionately.

One day Kamatha, seeing her alone, said: “Why do you waste away daily like a digit of the black half of the moon, fair-browed lady? Even if you do not tell it from shame, nevertheless I know your trouble. I think my younger brother, foolish, behaving like a eunuch, is the cause of that.” After hearing that improper speech of his, trembling, she began to flee, her hair and upper garment disheveled. Kamatha ran after her, held her by the hand, and said: “Foolish girl, why this fear* of yours at the wrong time? Bind up your loose hair and put on your garment which has fallen off.” these words he did it himself, though she was unwilling.

She said: “Elder brother, what is this? You are to be honored like Visvabhuti. This is not right for you or for leading to disgrace of both families.”

Kamatha smiled and said: “Do not say this from simplicity. Do not make your own youth, deprived of pleasured in vain. Enjoy pleasure of the senses with me, fair-eyed lady Enough of this eunuch Marubhuti now, since the law (smrti) is, ‘If the husband has disappeared, dies, become an ascetic, is impotent, or outcaste in these five calamities, of women another husband is prescribed.’”

So advised by him she, very desirous of pleasure in the beginning, seated on his lap first, abandoned shame together with propriety. Then Kamatha, wounded by love, dallied with her. In this way there were constantly secret opportunities always concealed, for them.

Finding this out, Varuna, bereft of compassion, red-eyed, jealous, told Marubhuti everything. Marubhuti said to her: “Lady, this ignoble conduct does not exist in the elder brother, like heat in the moon.” Though restrained by him in this way, she told that day after day. He reflected, “Who can be certain from confidence in someone else?” Being averse to sexual pleasure, in order to be a witness himself, he went to Kamatha and said, “I am going to the village now.” After saying this, Marubhuti went away, but returned at night in the guise of an exhausted begger by changing his dress and speech.

He said to Kamatha, “Sir, give me, a traveler from afar, shelter in your house,” and he gave it unhesitatingly. He stayed in the window shown him, pretending to go to sleep, wishing to see the evil conduct of the two blinded by love. Vasundhara and Kamatha, evil-minded, dallied for a long time, unafraid from the thought, “Marubhuti has gone to the village.” Marubhuti, staying where he was, saw what should not be seen, but did not do anything hostile, fearing people’s censure. He went and told everything to King Aravinda. Intolerant of evil conduct, he gave instructions to his guards:

“Kamatha, committing a crime, must not be killed because he is the son of the house priest. After seating him on a donkey with mockery, he is to be banished.”

After seating him on a donkey, they expelled Kamatha, his body spotted with mineral-mixtures, accompanied by drums sounding forth harshly. Watched by the townspeople, his head bent, unable to retaliate, Kamatha went to the forest, with a desire for emancipation. Then he became an ascetic under the ascetic Sivas and Kamatha began fool’s penance in the forest.229

Marubhuti suffered remorse: “Shame on what I did, that I told the king about my brother’s stumbling conduct. This stumbling of mine was greater than his stumbling. I shall go now and ask forgiveness of my elder brother.” With these thoughts, he asked the king and, though restrained by him, went to Kamatha and fell at his feet. Recalling the former disgrace at that time, Kamatha angrily raised a big stone and threw it at his head, as he was bowing. Taking it up even again, Kamatha threw the rock on him injured by the blow, as well as (throwing) himself completely into hell.

Now, Kamatha, unappeased by the murder of Marubhuti, not being made to speak by the guru, blamed by the other ascetics, died, engaged in especially painful meditation*; he became a kukkuta-serpent230 and roamed, destroying creatures like a winged Yama. One day as he roamed he saw the Marubhuti elephant* drinking pure water heated by the sun’s rays in a pool. He happened to be mired in mud at that time and was unable to get out because of his emaciation from penance and he was bitten on the boss by the kukkuta-serpent. Knowing his own death* (at hand) from the stream of the poison, the elephant rejected the four kinds of food*, engaged in concentrated meditation.*

Recalling the homage to the Five, engaged in pious meditation, he died and became a god in Sahasrara with a life-term of seventeen sagaras.

Varuna’s third incarnation

The cow-elephant Varuna practiced very severe penance, so that she became a goddess in the second heaven, after death.* There was no god in Isana whose heart was not won by her wealth of fascinating beauty and grace. But she did not pay any attention to any god at all, absorbed in thought of meeting the god with the soul of the elephant. The god with the soul of the elephant had great affection for her and, knowing by clairvoyance that she was in love, had her brought to Sahasrara.

The god made the goddess the crest-jewel of his harem. For affection connected with former births in very strong, Enjoying sensuous pleasure, suitable to the heaven Sahasrara, with her, he passed the time, foreseeing no separation.

Kamatha’s third incarnation

In course of time the kukkuta-serpent died and became a hell-inhabitant in the fifth hell, with a life-term of seventeen! sagaras. Kamatha’s soul always experienced pains suitable! for the fifth hell and never attained any rest at all.

Now, in the East Videhas in the province Sukaccha on Mt. Vaitadhya there is a city, named Tilaka, rich in money. In it there was a Khecara-lord, Vidyudgati by name, by whom all the Khecaras had been made to bow, like another Indra. His chief-queen was Kanakatilaka, who took the part of a tilaka of the harem from her wealth of beauty. Sometime passed as King Vidyudgati enjoyed sensuous pleasure with her.

And now the elephant* soul fell from the eighth heaven and descended into Queen Kanakatilaka’s womb. In the course of time she bore a son who had all the favorable marks of a man. He was named Kiranavega by his father. Cherished by nurses, he grew up gradually. He became the depository of arts and sciences and gradually attained youth. After requesting him, Vidyudgati had him take his kingdom and he himself took initiation under the guru Srutasagara.

Not greedy, he guarded his ancestral royal wealth and, not intent upon it, he enjoyed sensuous pleasure, intelligent. He had a son, Kiranatejas, the sole abode of splendor, borne by Padmavati. In course of time he became of military age with the sciences learned, noble, like a second form of Kiranavega. A muni, Suraguru, came there and made a stop. Kiranavega went there and bowed to him with great devotion, Then the sadhu delivered a sermon for the benefit of Kiranavega seated at his feet.

Sermon

“A human birth, which is capable of obtaining the fourth object of existence (emancipation), is very hard to win in this forest of births. A foolish man with an undiscerning soul, even when he has won it, wastes it in service to sense-objects, like a low person a fine jewel for a little money. Sense-objects, served for a long time, lead only to a fall into hell. Therefore, the dharma* taught by the Omniscient, which has emancipation as its fruit, must be served.”

After hearing this sermon which was like nectar to the ears, disgusted with existence, he placed his son, Kiranatejas, on the throne. He himself became a mendicant at the side of Suraguru and, after finishing his studies, became in course of time like an embodied chapter of traditional learning. With permission of his guru, he engaged in wandering alone. One day he went through the air to Puskaradvipa. After bowing to the eternal Arhats there he stood in pratima in a spot on Mt. Hema near Vaitadhya. The muni continued passing the time, practicing severe penance, enduring trials, sunk in tranquility.

Kamatha’s fourth incarnation

The soul of the kukkuta-serpent, having risen from hell, was born as a great serpent in a thicket of Mt. Hema. He wandered day and night in this forest for food*, destroying many creatures, like a long arm of Kala (Death*).

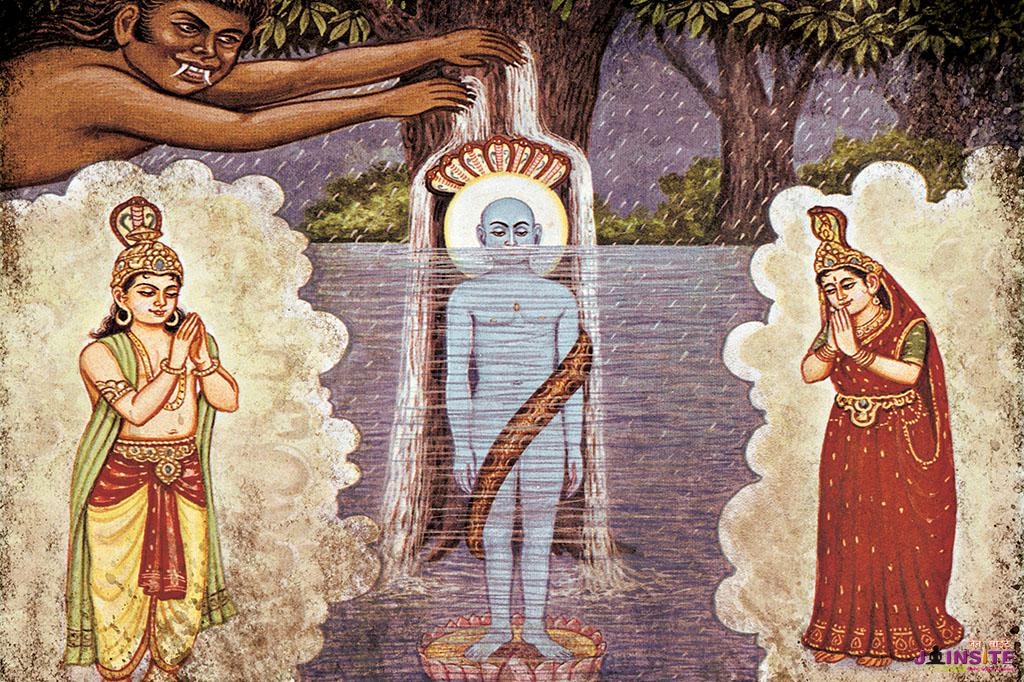

One day in his roaming the serpent saw Rsis Kiranavega standing in a bower, his mind fixed on meditation*, motionless as a pillar. Because of his hostility from a former birth, the serpent, red-eyed from anger, at once surrounded the sadhu, like a sandal tree, with coils. The serpent, pouring poison into his fangs, bit the muni in many places with fangs terrible with poison. The muni thought: “Surely this serpent is conferring great benefits on me for the destruction of karma; he is not causing injuries in the, least. Even if I lived for a long time, the destruction of karma must be made by me. Now it has been made by him. My purpose is accomplished in any case.”

Meditating in this way, he made confession, begged forgiveness from all the world, recalling the homage to the Five, engaged in pious meditation*, and observed a fast.

After death* he became a chief-god in the palace Jambudrumavarta in the twelfth heaven, with a life of twenty-two sagaras. Always sunk in pleasure there, brilliant with many kinds of magnificence, attended by gods, he passed the time.

Fifth incarnation of Kamatha

The serpent, roaming on Mt. Hema’s slope, was burned by a forest-fire and was born in the hell Dhumaprabha, with a life-term of seventeen sagaras. With a body of one hundred and twenty-five bows, he experienced there the sharp pains of hell, deprived of an atom of comfort.

Now in this Jambudvipa in the province Sugandha, the ornament of West Videha, there is a fine city, Subhankara by name. The king there, named Vajravirya, whose strength was irresistible, was like Indra in person, pious, the chief of the rulers of the earth. He had a chief-queen, Laksmivati by name, like another Laksmi in form, who had attained the ornamentship of the earth.

Kiranavega’s soul fell from Acyuta when its life-term had been completed, and descended into Laksmivati’s womb, like a hansa into a pool. At the right time she bore a son possessing a pure form, an ornament of the earth, named Vajranabha. Moon to the night-blooming lotus of the world, cherished by nurses, he gradually grew up, with joy to his parents. In course of time he attained youth, expert in weapons* and sciences; and he was installed on the throne by his father himself on a pure day. Vajravirya took the vow with his wife; but Vajranabha guarded properly the kingdom given by him.

In time there was a son, like another form of Vajranabha, named Cakrayudha, like Cakrayudha (Visnus) in strength. Cakrayudha the bee to the lotus-hands of nurses grew along with the desire for mendicancy on the part of his father who was terrified of worldly existence. Complete with the arts like the moon with digits, the prince attained youth and his father begged him: “Take the kingdom. But I, depressed by existence, the burden being taken now by you, shall undertake mendicancy, the only means of emancipation.”

Cakrayudha said: “Because of what fault committed from thoughtlessness and irresponsibility is there such disfavor to me? Pardon that, lord. Guard the kingdom as well as myself for a long time. Do not abandon me, father, after guarding me for so long.”

Vajranabha said: “There is no fault on your part, faultless one. But sons, like horses, are guarded for lifting a burden. Do you, having been born and having reached military age, fulfill my wish in the sphere of mendicancy now. For it has been known even from your birth. If I, even though you were born, weighed down by the burden, fall into the ocean of existence, then who will strive for good sons?” Saying this, the king installed him on the throne, though he was unwilling, by his own command. For the command of the elder is very powerful for the well-born.

Then the Blessed Jina, Ksemankara, came and stopped in a garden outside the city. After hearing that, Vajranabha thought: “The coming of the Arhat because of (my) merit is favorable to my wish.” He, wishing to become a mendicant, went with great magnificence at once and paid homage to the Jina, and listened to a sermon he delivered. At the end of the sermon, his hands folded in obeisance, he said to the Blessed One:

“Master, favor me by giving me the long-desired vow. Though I have acquired another good sadhu as guru because of merit, I have especial merit since you have come here as guru. I, wishing initiation, have installed my son on the throne now. I am ready for your favor characterized by giving mendicancy.”

The master himself at once initiated him saying this. He studied a section of the scriptures and practiced severe penance. Wandering alone by his guru’s permission, observing the pratima-posture, his body emaciated by penance, the great sage wandered in cities, et-cetera. By unbroken principal vows and firm lesser vows, the muni acquired in course of time the magic art of going-through-the-air, as if he had wings. One day flying up, the yatis went to the province Sukaccha, like another sun in the sky from his excessive brilliance from penance.

The serpent, after wandering through births after hell, was born in that very place in a great forest on Mt. Jvalana as a Bhilla, named Kurangaka. When he had grown up, he roamed daily in the forest with a strung bow, killing creatures for a livelihood. In his wandering Vajranabha reached that same forest inhabited by wild animals like soldiers of Antaka (Death*). Unterrified by the cruel animals, female yaks, et-cetera, the great sage went to Mt. Jvalana. Just then the sun set. From the habit of staying wherever he was when the sun set, he stayed in a cave of Mt. Jvalana in kayotsarga*, like a new peak of the mountain. Darkness spread over the directions, like a flock of flesh-eaters that had arisen. Owls with their hoots sounded like sporting birds of Death. Wolves howled aloud like singers belonging to Raksases; tigers wandered, striking the ground with their tails like a drum with drum-sticks. Witches in various forms, female demons, female Vyantaras, by whom cries of “Kila! kila!” were made, met at that time by agreement. The Blessed One, motionless, remained at that same time and in that same place very terrifying by nature, fearless as if he were in a garden. As he was practicing meditation*, the night passed and the light of the sun appeared, like the light of his penance. Then the muni set out to wander over the earth whose creatures had gone from the touch of the sun’s rays, his gaze fixed at the distance of six feet. Just then the hunter Kurangaka came forth, cruel as a tiger, wearing a tiger-skin, carrying a bow and quiver. Then he saw muni Vajranabha approaching and he became exceedingly angry, thinking, “This ascetic is a bad omen.” Angry because of the hostility of previous births, his bow drawn at a distance, Kurangaka struck down the great sage like a deer. Reciting, “Homage to the Arhats,” he sat down, after brushing off the surface of the ground, free from painful meditation, though he was wounded by the blow. After confessing fully to the Siddhas, he undertook a fast, asked pardon of everyone, being especially free from attachment.

Engaged in pious meditation he died and became a god of the highest magnificence, named Lalitanga, in the middle Graiveyaka.

Seventh incarnation of Kamatha

After seeing him dead from one blow, feeling pride, Kurangaka rejoiced at the thought, “I am a great bowman.” After living from hunting from birth, Kurangaka died and was born in the abode Raurava in the seventh hell.

Now, in this Jambudvipa in the East Videhas there is a broad city, Puranapura, resembling a city of the gods.

Kulisabahu, resembling Indra (Kulisabhrt), was king there, his command borne like a wreath by hundreds of kings. His chief-queen was Sudarsanas, fair in form, the recipient of extreme affection. He experienced pleasures of the senses, sporting with her like the earth embodied, without doing injury to the other objects of existence.

His life completed, in course of time the god Vajranabha fell from Graiveyaka and descended into her womb. At dawn, lying on her couch, Queen Sudarsana saw the fourteen great dreams indicating the birth of a cakrabhrt. Delighted by the dreams as explained by her husband, she passed the time. At the right time she bore a son, like the east bearing the sun.

After holding the birth-festival, the king gave him the name, Suvamabahu, with a great festival again. Being passed from lap to lap by nurses and kings, he crossed childhood slowly, like a traveler a river. He learned all the arts easily from the impression on his mind from previous births and he reached fresh youth, the abode of Love. Suvamabahu was without a counterpart in the world in beauty, invincible in courage, and gentle with a wealth of good-breeding. The king, depressed by existence, knew that his son was competent and, after importuning him, installed him on the throne, but became a mendicant himself. With his command unbroken on earth he (Suvamabahu), like Indra in Saudharma, continued to enjoy pleasures, immersed in the nectar of happiness.

One day he went out for sport, attended by thousands of kings, mounted on a new horse that was like an eighth horse of the Sun’s horses.231 Wishing to test the horse’s speed, the king struck him with a whip and he ran away very fast like a deer, a mount of Marut.232 The more the king pulled on the bridle, the faster he ran because of inverted training. Like Garuda on foot, like the wind embodied, the horse outdistanced the soldiers in a moment. Whether touching the earth or going through the air, the horse could not be seen because of his speed. It was conjectured, “The king has gone with him, certainly, mounted on him.”

In a moment the king reached a forest very far away, full of various trees, crowded with all kinds of animals. The king saw a pool spotless as his own heart and the horse, thirsty, panting hard, stopped at the sight of it. Then the king took off the saddle, bathed and watered the horse; and the king himself bathed and drank. Then after coming out (of the pool) and resting a moment on its bank, the king started out and saw ahead a charming ascetics grove. The king was delighted, seeing it with trees whose water-basins were being filled by young ascetics holding young deer on their hips.

As the king was entering it, his right eye twitched, indicating new happiness to him expert in proper procedure. As he went forward, delighted, the king saw on the right a girl-ascetic with a girl-friend sprinkling the trees with pitchers of water. He thought, “Indeed, there is no such beauty of the Apsarases nor of the Naga women, nor of mortal women. She is superior to the three worlds.” While the king, hidden in the trees, was considering her, she entered a bower of madhavi233 with her friend. After loosening the firmly-fastened bark-garment, the maiden began to sprinkle the bakulaB, her mouth giving joy to the bakula.234 Again the king reflected: “On the one hand, the beauty of her, lotus-eyed; on the other hand, this work suitable for an ordinary woman. She is not an ascetic-maiden, since my mind is attached to her. Surely she is some princess who has come here from some place.”

Just then a bee flew into her face with the idea that it was a lotus, causing terror to her shaking two fingers. When the bee did not leave her, then she said to her friend, “Save me from this Raksasa of a bee. Save me! “The friend said: “Who is able to save you except Suvamabahu? Follow the king alone, if your object is protection.”

“Who, pray, threatens you, when the son of Vajrabahu235 is protecting the earth?” With these words the king, knowing that it was a suitable time, appeared before them. Seeing him suddenly, they were alarmed and did not do or say anything suitable. Knowing they were frightened, the king said to them; again, “Does someone interfere with your unhindered penance here, fair lady?”

Regaining composure, the friend said: “While Vajrabahu’s son is king, who is able to make an obstacle to penance of ascetics here? This girl was only stung on the face by a bee with the idea that it was a lotus. The timid-eyed maiden said, ‘save! Save!’ “The king sat down on a seat which she offered at the foot of a tree and was questioned by her with a pure mind in a voice like nectar.

“You are shown to be someone uncommon by your form which is beyond criticism. Then say who you are a god or a Vidyadhara?” The king himself was unable to name himself and said: “I am the attendant of King Kanakabahu. At his order I have come here to the hermitage to restrain those causing obstacles.* The king’s effort in this is great.”

The king said to the friend who was thinking, “He is the king himself,” “Why is the girl tormented by that work?”

Sighing, she said: “She is the daughter, Padma, borne by Ratnavali, of the Khecara-king, lord of Ratnapura. Her father died as soon as she was born and his sons, seeking his kingdom, fought with each other and destruction of the kingdom, took place. Ratnavali took this girl and came to the house in the hermitage of her brother, Abbot Galava. One day a sadhu who had divine knowledge came here and Galava asked him, “Who will be Padma’s husband?” The great muni replied, “The son of Cakrabhrt Vajrabahu, come hither, carried away by his horse, will marry the girl.”

The king reflected: “This sudden running away of the horse with me is surely a design of the Creator for union with her.” He said: “Lady, tell me where the abbot is now. At the sight of him now may I have a shoot of joy.”The friend replied: “He has gone now to follow the muni who has started to wander elsewhere. After he has paid homage to him, he will return.” Then an old sadhvi said: “Oh, Nanda,236 bring Padma. It is time for the abbot’s return.” The king, by whom the arrival of soldiers was known from the noise of the horses hooves, said, “You go. I shall keep the army from the hermitage.” Then Padma was led away from the place by Nanda with difficulty, as she was looking at King Suvamabahu, her head turned. The abbot and Ratnavali came at that time and the friend told the story of Suvamabahu excitedly.

Galava said: “The muni’s knowledge is exceedingly trust-worthy. The noble Jain sages do not speak anything false. He, the chief of the caste and order, must be honored with hospitality. And he is Padma’s future husband. We will go with Padma to him.” Then the abbot, accompanied by Ratnavali, Padma, and Nanda, went to the king’s presence and was honored by the king who had risen.

The king said to Galava: “Eager to see you today, I have wished to come. But why have you yourself come?”

Galava said: “Anyone else who has come to the hermitage must be honored with hospitality, but specially you, our protector. An omniscient predicted that Padma here, my sister’s daughter, would be your wife. You have come because of her merit. So, marry her now.”

So advised by the muni, Svamabahu married Padma, like another Padma (Laksmi), with Gandharva rites. Then Ratnavali said to the king, who held a festival, “Always be the sun to the lotus of Padma’s heart.” Just then Ratnavali’s son, Padmottara, a king of Khecaras, came to that place with his wives, bringing gifts, covering the sky with aerial cars. He came to the place and, announced by Ratnavali, after bowing to Svamabahu with hands folded respectfully, he said:

“After learning this story of yours, I have come here to serve you alone, Majesty. So give me your orders, king. Do you, rich in splendor, come to my city on Mt. Vaitadhya. There the Laksmi of the lordship of the Vidyadharas awaits you.”

At his importunity the king assented to his proposal. Padma bowed to her mother and said with sobs: “I shall go with my husband, mother. Henceforth, there is no home for me elsewhere. So tell me. When shall I see you again? Alas! How shall I abandon the trees of the garden like brothers, the young deer like sons, the ascetic-maidens like sisters! Before whom will the peacock display the art of the tandava with a voice pleasing with the sixth note, when the cloud thunders? Without me who will now make the bakulaB, asokaB, and mangoB trees drink water, like sons drinking milk, mother?

Ratnavali said: “Child, you have become the cakravartin’s wife. Then forget, alas! your mode of life resulting from living in the forest. You must now follow your husband, the cakrin, Vasavas on earth. You will be a queen in his abode of joy. Enough of sorrow.” After saying this, kissing her on the head, embracing her ardently, and taking her on her lap, Ratnavali, shedding tears, advised her:

“Child, when you have gone to your husband’s house, always be submissive. Eat, when your husband has eaten, Lie down, when he has lain down. The cakrin’s wife, you must always treat co-wives with courtesy, even though they practice rivalry. For that is suitable for greatness. Your face covered by a veil, your eyes always downcast, child, you should adopt not-seeing-the sun, like a night-blooming lotus. You should practice attendance at your father-in-law’s lotus-feet, like a hansi; by all means do not show pride caused by being the cakrin’s wife. Always consider your husband’s children by co-wives like your own nurslings and have them come to the couch of your lap.”

After drinking the nectar of this speech of advice with the hollows of her ears and after bowing to her, she took leave of her mother and became a follower of her husband. Padmottara, after bowing to Ratnavali, said to the King, “Adorn my aerial car, master.”

Then the king took leave of Gavala and Ratnavali and got into Padmottara’s car with his attendants. Then Padmottara conducted Svamabahu accompanied by Padma to the city Ratnapura, the crown on the head of Vaitadhya. The Khecara gave King Svamabahu a palace made of jewels like a palace of the gods. Obeying orders, standing at his side like a servant of the king, he arranged the usual procedure with bath, food*, et-cetera. Staying there, Svamabahu attained lordship over all the Vidyadharas in the two rows by a great wealth of merit. He married many Vidyadhara-maidens there and was consecrated in lordship over all Vidyadharas by the Vidyadharas. Then accompanied by the Khecaris, Padma and others, whom he had married, Svamabahu went to his own city with his retinue.

The fourteen great jewels gradually appeared to King Suvamabahu ruling the earth properly. Following the path of the cakra, he subdued the six-part orb of the earth with ease, attended even by gods. Sporting with various sports, Vajrabahu’s son remained there, surpassing all brilliance by (his own) brilliance, like the sun.

One day, when he was on top of the palace, he saw with astonishment a group of gods flying up and down in the air. He heard that the Lord of the World, the Tirthanatha, had come and he went to pay homage to him, his mind filled with faith. After paying homage to the Jinendra and sitting down in the proper space, he listened to a sermon from him, which resembled unexpected nectar. After enlightening many souls capable of emancipation, the Blessed One went elsewhere. King Suvamabahu went to his own house.

The king recalled again and again the gods who had come to the Tirthakrt’s sermon, “Where have I seen them before?” and reached remembrance of former births by using uha and apoha. Seeing his former births, he reflected:

“To me striving for Human birth, there is no end to existence by that (human birth). One, who has attained the state of a god, delights in mortal state. What bewilderment is this of the soul whose nature is hidden by karma? A creature goes to heaven, the world of mortals, an animal birth, and hell, lost from the road to emancipation, like a traveler on different roads. Therefore, I shall strive especially for the road to emancipation only. The wealth of self-reliance is the root of every purpose.”

After making this decision, King Svamabahu installed his son on the throne. At that time the Lord Jina, the Lord of the World, came in his wandering. Vajrabahu’s son went to the Tirthanatha’s presence and became a mendicant. Practicing severe penance, he finished his studies in time. By means of some of the sthanas, devotion to the Arhats, et-cetera, being practiced, he, intelligent, gradually acquired the body-making karma of a Tirthakrt. One time in his wandering he went to a great forest, Ksiravana, terrifying from various wild animals, near Mt. Ksira. There, facing the sun, like another sun in brilliance, he continued practicing penance, maintaining firm statuesque posture.

Kurangaka, risen from hell, became a lion on that mountain and by chance came there in his roaming. Hungry because he had not obtained food* the day before, he, resembling Death*, saw the great sage from a distance. Angry from hostility of former births, the lion ran forward, his mouth wide open, splitting open the earth, as it were, with blows of his tail. The lion with ears erect, filling the caverns with loud roars, approaching by leaps, made an attack on the muni from the ground. The muni, knocked to the ground by the lion, free from desire for the body, made rejection of the four kinds of food, engaged in concentrated meditation.* The muni made confession, asked forgiveness of all creatures, and continued in pious meditation, his heart unchanged even toward the lion.

Torn by the lion, the muni died and became a god in the palace Mahaprabha in the tenth heaven, with a life-duration of twenty sagaras.

Ninth incarnation of Kamatha

The lion, too, died and went to the fourth hell with a life-duration of ten sagaras. He was born in animal-births, experiencing many and various pains.

Then the lion’s soul, experiencing pains in worldly existence, was born as a son in a poor Brahman family in some hamlet. His father, brothers, et-cetera had died soon after he was born. He had been kept alive by the people from compassion; and he was called Kamatha. He survived childhood and had reached youth, always in a miserable condition. Ridiculed by the people, he got food* with difficulty.

One day, seeing rich men wearing jewels and ornaments, disgust with existence having developed at once, Kamatha reflected: “These thousands of gluttons, adorned with various ornaments, are like gods. I think that is the fruit of penance in a former birth. I, always craving mere food, surely did “Not perform penance. So I shall practice penance now.” Reflecting to this effect, from desire for emancipation, he1 took the vow of an ascetic and practiced the penance of the five fires, et-cetera, his food consisting of bulbs, roots, et-cetera.

Incarnation as Parsvanatha

Now in this Jambudvipa, there is a city, Varanasi, on the Gangas, the ornament of Bharataksetra. Banners on its shrines looked like waves of the Jahnavi. The golden finials were like lofty lotus-calyxes. The rays of the full moon, rising above its wall, gave the appearance of a silver coping at night. Maidens, who are guests in the houses there whose floors are paved with sapphire, are laughed at because they put their hands (on the floors) with the idea that they are water. Its shrines with rising smoke of burned incense, that was like blue garments that had been put on, shone for the destruction of the evil-eye.237 The peafowl there utter their cries all the time as if it were the rainy season, mistaking the sounds of drums in concerts for thunder of the clouds.

Parsva, playing in a playhouse, heard the sound of the drum and the noise of the soldiers assembling at that time. Saying, “What is this?” Parsva, perplexed, went to his father’s side and he saw the generals ready for battle coming there. After bowing to his father, the prince said decisively: “Has a demon, a Yaksa, a Raksasa, or someone else transgressed? On account of which there is this exertion of the father himself, powerful? I do not see anyone your equal or your superior.”

Pointing to Purusottama, Asvasena said, “King Prasenajit must be protected from King Yavana.” Again the prince said: “Compared with the father there is no god nor asura in battle. Of what importance is this King Yavana in the matter? Enough of the father’s going. I shall go myself. I shall at once give a lesson to him who does not know (his own) strength.”

Asvasena said: “Son, my mind is pleased by your festival of sport, not by injurious battle-marches, et-cetera. I know the strength of arm, capable of conquering the three worlds, of my own son, but my delight is in you playing in the house.”

Parsvanatha replied: “This is play for me, father. There is no measure* of effort in it. So let Your Honor remain right here.”

At his son’s insistence like this, knowing his strength of arm, he agreed to that speech devoid of anything objectionable. Dismissed by his father, Sri Parsva, mounted on an elephant*, followed by Purusottamas, set out at an auspicious* moment from the festival. When the lord had gone one day’s march, Sakra’s charioteer came, bowed, got down from his chariot and said with folded hands:

“Indra, knowing that you wish to fight for sport, master, sent a battle-chariot with me as a charioteer. He knows that the three worlds are like straw compared with the master’s strength. Nevertheless, Sakras shows his devotion to you at the right time.”

As a favor to Sakra, the Master got into the great chariot filled with various weapons*, which did not touch the surface of the ground. Sri Parsvanatha advanced, hymned by the Vidyadharas, with the chariot going through the air, with great splendor like the sun. The Lord’s army, skilled in battle, adorned with soldiers looking up to see the Master again and again, followed on the ground. The Master, able to go in a moment, alone competent for victory, went with short marches at his soldiers request. In some days he reached Kusasthala and then camped in a seven-storied palace made by the gods in a garden.

“This is the custom of warriors,” the Lord, impelled by compassion, sent an intelligent messenger with instructions to Yavana. He went to Yavana and said eloquently from the Master’s power: “Prince Srimat Parsva instructs you by my mouth: ‘King Prasenajit, who has sought protection from my father, must be freed from the siege and hostility by you now, O king. I, after restraining with difficulty my father who had started, have come to this country merely for that reason. Return to your own place. Submit at once. This transgression* of yours can be tolerated only if you go away.’ “

Yavana, his brow terrible from frowns, said: “Messenger, why do you say this! Do you not know me? Who is this boy Parsva who has come here for battle from a caprice? Who is the old man Asvasena who started first? Both of them and other kings, their partisans what do they amount to? Therefore, go! Let Parsva go also with the desire for his own welfare. You are not to be killed because you are a messenger, though saying harsh things. Escaping alive, go and tell everything to your master.”

Again the messenger said: “The lord sent me to enlighten you from compassion, not from weakness, evil-minded man. As the lord wishes to protect the King of Kusasthala, likewise he does not wish to kill you, if you obey his command, sir! Breaking the master’s command, unbroken even in heaven, you die yourself, like a stupid moth touching a bright fire. On the one hand, a fire-fly; on the other, a sun lighting up the whole universe. On the one hand, you are a mere king; on the other, Parsva, the lord of three worlds.”

Yavana’s soldiers, their weapons* raised, rose up angrily and said defiantly to the messenger saying this: “Is there some hostility of yours toward your own master that you make this threat, villain? You are well-skilled in stratagem, wretch! “While they were talking in this way and wishing to kill him from anger, an old minister said in contemptuous and harsh words: “He is not an enemy of his master, but you are an enemy (of yours) who thus cause injury to your lord from your own desire. To cross the command of Parsvanatha, lord of the universe, is not for your welfare, fools, to say nothing of killing his messenger. The master is thrown at once into a thicket of evil by such servants like untamed horses that have dragged him along. Messengers of other kings have been attacked before by you. In those cases it turned out well for you, for our lord was stronger than they. What is this quarrel

of our lord, caused by badly-behaved worms of men, with one of whom the sixty-four Indras are servants! “

All the soldiers, reprimanded in this way, terrified, became quiet. Taking the messenger by the hand, the minister spoke with conciliation.”What these men, who make their living by arms alone, said to you from ignorance, you must pardon. You are a wise servant, for ocean of tolerance. We shall follow you ourselves to take the honored Parsva’s commands on our head. Do not tell such a thing to your lord.” After informing the messenger to this effect and entertaining him, he dismissed him.

Desiring his welfare, he said earnestly to his own lord: “Master, was this, which has evil consequences, done after reflection? (But) even by so much there is not ruin. Resort to Parsvanatha whose birth-rites goddesses performed, whose nurse-duties goddesses discharged, whose birth-bath the Indras and gods gave. What is this inclination of yours for a quarrel with him, of whom gods and asuras with the Indras are footmen, like that of a goat with an elephant*? Here Garuda, there a raven; here Meru, there a mustard-seed; here the serpent Sesa, there a heron-snake; here Parsva, there such as you, As soon as you are allowed by the people, then with desire for your own good tie an axe to your neck and approach Asvasena’s son. Accept the rule of Parsva Swamin, ruler of the world. The ones who are under his rule are fearless in this world and the next.”

After reflection Yavana said: “I have been well enlightened by you. I, stupid, have been saved from this evil, like a blind man from a well.” With these words, Yavana tied an axe to his neck and with his retinue went to the garden adorned with Sri Parsva Syamin. Yavana was extremely astonished when he saw his army adorned with seven lacs (of soldiers) resembling horses of the sun; with bhadra elephants by the thousand resembling elephants of Mahendra; with chariots like aerial cars of the gods; with foot-soldiers like Khecaras.

Being watched at every step by the soldiers with astonishment and scorn, gradually Yavana arrived at the door of the Master’s palace. He was announced by the door-keeper and, admitted to the council, bowed from a distance to the lord like the sun. The axe on his neck being removed by the master, Yavana bowed again, approached before him, and said, his hands folded respectfully:

“Compared with him, whose commands all the Indras execute, what am I a worm of a man, a heap of straw before a fire! Showing compassion, just now you gave me orders by sending a messenger. Why am I not reduced to ashes merely by your frown? This rude behavior of mine has become a virtue, master, since I have seen you purifying the three worlds. How can I say, ‘Pardon,’ when there is no anger on your part? To say, ‘I give,’ to you, yourself lord of the house, is not suitable. ‘I am your servant,’ is a poor speech to you who are served by Indras. What sort of speech is, ‘Give freedom from fear*,’ to the bestower of fearlessness himself? Nevertheless, from ignorance I say, ‘Be gracious. Take my wealth. I am your servant. Bestow freedom from fear on me, terrified, lord.’”

Parsva, playing in a playhouse, heard the sound of the drum and the noise of the soldiers assembling at that time. Saying, “What is this?” Parsva, perplexed, went to his father’s side and he saw the generals ready for battle coming there. After bowing to his father, the prince said decisively: “Has a demon, a Yaksa, a Raksasa, or someone else transgressed? On account of which there is this exertion of the father himself, powerful? I do not see anyone your equal or your superior.”

Pointing to Purusottama, Asvasena said, “King Prasenajit must be protected from King Yavana.” Again the prince said: “Compared with the father there is no god nor asura in battle. Of what importance is this King Yavana in the matter? Enough of the father’s going. I shall go myself. I shall at once give a lesson to him who does not know (his own) strength.”

Asvasena said: “Son, my mind is pleased by your festival of sport, not by injurious battle-marches, et-cetera. I know the strength of arm, capable of conquering the three worlds, of my own son, but my delight is in you playing in the house.”

Parsvanatha replied: “This is play for me, father. There is no measure* of effort in it. So let Your Honor remain right here.”

At his son’s insistence like this, knowing his strength of arm, he agreed to that speech devoid of anything objectionable. Dismissed by his father, Sri Parsva, mounted on an elephant*, followed by Purusottamas, set out at an auspicious* moment from the festival. When the lord had gone one day’s march, Sakra’s charioteer came, bowed, got down from his chariot and said with folded hands:

“Indra, knowing that you wish to fight for sport, master, sent a battle-chariot with me as a charioteer. He knows that the three worlds are like straw compared with the master’s strength. Nevertheless, Sakras shows his devotion to you at the right time.”

As a favor to Sakra, the Master got into the great chariot filled with various weapons*, which did not touch the surface of the ground. Sri Parsvanatha advanced, hymned by the Vidyadharas, with the chariot going through the air, with great splendor like the sun. The Lord’s army, skilled in battle, adorned with soldiers looking up to see the Master again and again, followed on the ground. The Master, able to go in a moment, alone competent for victory, went with short marches at his soldiers request. In some days he reached Kusasthala and then camped in a seven-storied palace made by the gods in a garden.

“This is the custom of warriors,” the Lord, impelled by compassion, sent an intelligent messenger with instructions to Yavana. He went to Yavana and said eloquently from the Master’s power: “Prince Srimat Parsva instructs you by my mouth: ‘King Prasenajit, who has sought protection from my father, must be freed from the siege and hostility by you now, O king. I, after restraining with difficulty my father who had started, have come to this country merely for that reason. Return to your own place. Submit at once. This transgression* of yours can be tolerated only if you go away.’ “

Yavana, his brow terrible from frowns, said: “Messenger, why do you say this! Do you not know me? Who is this boy Parsva who has come here for battle from a caprice? Who is the old man Asvasena who started first? Both of them and other kings, their partisans what do they amount to? Therefore, go! Let Parsva go also with the desire for his own welfare. You are not to be killed because you are a messenger, though saying harsh things. Escaping alive, go and tell everything to your master.”

Again the messenger said: “The lord sent me to enlighten you from compassion, not from weakness, evil-minded man. As the lord wishes to protect the King of Kusasthala, likewise he does not wish to kill you, if you obey his command, sir! Breaking the master’s command, unbroken even in heaven, you die yourself, like a stupid moth touching a bright fire. On the one hand, a fire-fly; on the other, a sun lighting up the whole universe. On the one hand, you are a mere king; on the other, Parsva, the lord of three worlds.”

Yavana’s soldiers, their weapons* raised, rose up angrily and said defiantly to the messenger saying this: “Is there some hostility of yours toward your own master that you make this threat, villain? You are well-skilled in stratagem, wretch! “While they were talking in this way and wishing to kill him from anger, an old minister said in contemptuous and harsh words: “He is not an enemy of his master, but you are an enemy (of yours) who thus cause injury to your lord from your own desire. To cross the command of Parsvanatha, lord of the universe, is not for your welfare, fools, to say nothing of killing his messenger. The master is thrown at once into a thicket of evil by such servants like untamed horses that have dragged him along. Messengers of other kings have been attacked before by you. In those cases it turned out well for you, for our lord was stronger than they. What is this quarrel of our lord, caused by badly-behaved worms of men, with one of whom the sixty-four Indras are servants! “

All the soldiers, reprimanded in this way, terrified, became quiet. Taking the messenger by the hand, the minister spoke with conciliation.”What these men, who make their living by arms alone, said to you from ignorance, you must pardon. You are a wise servant, for ocean of tolerance. We shall follow you ourselves to take the honored Parsva’s commands on our head. Do not tell such a thing to your lord.” After informing the messenger to this effect and entertaining him, he dismissed him.

Desiring his welfare, he said earnestly to his own lord: “Master, was this, which has evil consequences, done after reflection? (But) even by so much there is not ruin. Resort to Parsvanatha whose birth-rites goddesses performed, whose nurse-duties goddesses discharged, whose birth-bath the Indras and gods gave. What is this inclination of yours for a quarrel with him, of whom gods and asuras with the Indras are footmen, like that of a goat with an elephant*? Here Garuda, there a raven; here Meru, there a mustard-seed; here the serpent Sesa, there a heron-snake; here Parsva, there such as you, As soon as you are allowed by the people, then with desire for your own good tie an axe to your neck and approach Asvasena’s son. Accept the rule of Parsva Swamin, ruler of the world. The ones who are under his rule are fearless in this world and the next.”

After reflection Yavana said: “I have been well enlightened by you. I, stupid, have been saved from this evil, like a blind man from a well.” With these words, Yavana tied an axe to his neck and with his retinue went to the garden adorned with Sri Parsva Syamin. Yavana was extremely astonished when he saw his army adorned with seven lacs (of soldiers) resembling horses of the sun; with bhadra elephants by the thousand resembling elephants of Mahendra; with chariots like aerial cars of the gods; with foot-soldiers like Khecaras.

Being watched at every step by the soldiers with astonishment and scorn, gradually Yavana arrived at the door of the Master’s palace. He was announced by the door-keeper and, admitted to the council, bowed from a distance to the lord like the sun. The axe on his neck being removed by the master, Yavana bowed again, approached before him, and said, his hands folded respectfully:

“Compared with him, whose commands all the Indras execute, what am I a worm of a man, a heap of straw before a fire! Showing compassion, just now you gave me orders by sending a messenger. Why am I not reduced to ashes merely by your frown? This rude behavior of mine has become a virtue, master, since I have seen you purifying the three worlds. How can I say, ‘Pardon,’ when there is no anger on your part? To say, ‘I give,’ to you, yourself lord of the house, is not suitable. ‘I am your servant,’ is a poor speech to you who are served by Indras. What sort of speech is, ‘Give freedom from fear*,’ to the bestower of fearlessness himself? Nevertheless, from ignorance I say, ‘Be gracious. Take my wealth. I am your servant. Bestow freedom from fear on me, terrified, lord.’”

Sri Parsvanatha said: “Good fortune to you, sir. Do not fear. Rule your kingdom. Do not do such a thing again.” The Teacher of the World rewarded him, who agreed to this, by the gift of much favor. For such is the custom of the great. At once the siege of Kusasthala was raised and Purusottamas left, after obtaining permission from Parsvanatha. He related the story to King Prasenajit and joy became the sole umbrella in the city at that time.

Prasenajit reflected, pleased: “I am fortunate in every way and my daughter Prabhavati is fortunate in every way. The wish Prince Parsvanatha, worshipped by gods and asuras, will purify my city has not taken place. Taking this same Prabhavati as a present, I shall go to Prince Parsvanatha, a benefactor.” After these reflections, Prasenajit, delighted, went with a delighted retinue to Parsvanatha, taking Prabhavati.

With folded hands he bowed to Parsva Swamin and said: “By good fortune, your arrival, master, was like rain without clouds. Yavana, though an enemy, was a benefactor to me in the quarrel because of which you, the lord of three worlds, did me a favor. As you did me a favor from compassion by coming here, likewise do me a favor by marrying Prabhavati. She, seeking what is hard to obtain, is infatuated with you from a distance. Show compassion for her. You are compassionate by nature.”

Prabhavati thought: “The prince, formerly heard about from Kinnaris is now seen. The eye agrees with the ear. Courteous in speech, compassionate, he is heard and seen. Now he is well importuned by my father for my sake. Yet I am frightened now from lack of confidence in my good fortune, filled with anxiety whether or not he will approve my father’s proposal.”

While she was thinking this, Prince Parsva, his voice deep as thunder, said to Prasenajit who was waiting: “By the father’s command we have come to protect you, Prasenajit, but not to marry this daughter of yours. So do not insist on this uselessly, Lord of Kusasthala. Having executed the father’s command, we are going to the father’s presence.”

Hearing that, Prabhavati, very depressed, thought: “Such a speech from him is like a fall of fire from the moon. He was compassionate to everyone, but cruel to me. How will you exist, alas! unfortunate Prabhavati? Family deities always worshipped, now show my father some device at once. For his devices are destroyed now.”

Prasenajit thought: “He himself is free from all desire, but he will do what I wish at Asvasena’s insistence. I shall go with him under pretext of wishing to see Asvasena. I shall importune Asvasena to accomplish that wish.” Having caused friendship to be made with him so reflecting, Parsvanatha honored and dismissed King Yavana. Prasenajit, being dismissed, said to Parsvanatha, “I shall go, wishing to bow to honored Asvasena, lord.” Taking Prabhavati, he went with Sri Parsva, who had said, “Very well,” to the city Varanasi.

Pleasing Asvasena by the protection of those who had come for protection, Parsvanatha approached and made him rejoice by the sight of himself. When Parsva had gone to his own house, Prasenajit approached and went before him, accompanied by Prabhavati. Asvasena rose to greet him, raised him falling at his feet, embraced him with both arms, and said, perplexed:

“I hope your rescue took place. I hope that things are well with you, king. I wonder what the reason is that you have come here yourself.”

Prasenajit said: “Always I, of whom you, a sun in splendor, are the ruler, have protection and prosperity. But the request for something hard to obtain alone troubles me now. It will be accomplished by your favor, elephant* of kings. Take my daughter, Prabhavati, for Prince Parsvanatha from regard for me, king. Do not do otherwise.”

Asvasena said: “Our Prince Parsva has always been disgusted with worldly existence. I do not know what he will do. That desire of ours, too, is always in our heart: ‘When will our son’s marriage-festival with a suitable bride take place?’ Now from, affection for you we shall make Parsvanatha marry, even by force, though he has been unwilling from childhood.”

With these words, the king went with him to Parsva and said, “Marry Prasenajit’s daughter.” Sri Parsva said: “Father, possession of wives, et-cetera is a life-saver of the tree of worldly existence even when it is almost destroyed. How can I marry his daughter for undertaking worldly existence? I intend to cross the ocean of worldly existence, completely free of possessions.

As the Lord wandered, his retinue from the day of omniscience consisted of sixteen thousand rsis (sadhus), thirty-eight thousand noble sadhvis, three hundred and fifty who knew the fourteen purvas*, fourteen hundred who had clairvoyant knowledge, seven hundred and fifty who had mind-reading knowledge, one thousand omniscients, eleven hundred who had the art of transformation, six hundred noble disputants, one lac and sixty-four thousand laymen, and three lacs and seventy-seven thousand laywomen.

His emancipation

Knowing that his emancipation was near, the Lord went to Mt. Sammeta, accompanied by thirty-three munis, and fasted for a month. The Teacher of the World, together with the thirty-three munis, attained the place from which there is no return on the eighth of the white half of Sravana, (the moon being) in Visakha.

Thirty years as householder, seventy in keeping the vows so the age of Sri Parsva Swamin was one hundred years. The emancipation of the Supreme Lord, Sri Parsvanatha, took place eighty-three thousand, seven hundred and fifty years from the day of Sri Nemi’s emancipation. The lords of gods, Sakras and the others, came to Mt. Sammeta’s peak, accompanied by the gods. Subject to an excess of grief, they celebrated splendidly the emancipation-festival of the Supreme Lord, Parsva.

The ones who, believing, bring the biography of Parsvanatha, purifying the three worlds, within the range of hearing from them misfortunes go away; and they would be remarkably prosperous, and they go to the final abode. What else?

He then asked the Lord: “Because of what acts did six wives die as soon as married and why did my separation and imprisonment take place?” The Master related:

“Here in Bharata on Mt. Vindhya there was a Sabara-lord, named Sikharasena, intent on doing harm, devoted to sense-objects. Priyadarsana was his wife, named Srimati, and you continued playing with her in mountain-thickets at that time. One day a group of sadhus, who had lost the way, came there wandering in the forest and was seen by you with a compassionate mind. You went and asked the sadhus, ‘Why do you wander here?’ They told you, ‘We have lost the way.’

Srimati said to you, ‘After feeding them with fruit, et-cetera, help these munis cross the Vindhya-forest difficult’ to cross. You brought bulbs, et-cetera and they said: ‘This is not proper. If there is anything devoid of color, odor, et-cetera, give us that. Or fruit, et-cetera, that was gathered a long time ago, is suitable for us.’ On hearing that, you fed them with such bulbs, et-cetera. You led the sadhus to the road and they taught dharma.* After giving you the formula ‘homage to the five,’ they instructed you as follows:

‘On one day in a fortnight you, staying in solitude, with all censurable activity given up, must recall this formula of homage. If someone should threaten you then, do not be angry at him. If you practice dharma in this way, the glory of heaven is not hard to attain.’ You said, ‘So be it.’

One day a lion approached you as you were doing just so and Srimati was at once afraid of him. Saying, ‘Do not be afraid,’ you seized a large bow, (but) you were reminded by Srimati of the self-control advised by the guru. Then you, motionless, and noble Srimati were devoured by the lion and you became gods in Saudharma with a life-term of a palya.*

After falling, you became the son of King Kurumrganka and Balacandra in Cakrapuri in the West Videhas. Srimati, falling from heaven, became the daughter of King Subhusana, brother-in-law of Kurumrganka, and Kurumati. You two, Vasantasena and Sabaramrganka by name, gradually attained youth, living in your respective places. She fell in love with you from hearing your virtues; and you with her from the sight of a painting of her figure brought by an esteemed painter. You were married to her by your father, knowing your affection. Your father became an ascetic and you became king. At that time the karma originating in your Bhilla-birth, caused by separating animals, matured. Hear the full truth, noble sir.

In that same province, a powerful king, lord of Jayapura, named Vardhana, angry for no reason, said to you through agents: ‘Send me Vasantasena and accept my command. In that case enjoy your kingdom; if not, fight with me.’ Hearing that with anger, mounted on an elephant*, you set out with an army for battle, being prevented by the people from seeing unfavorable omens. At that time King Vardhana, being defeated, fled; and a powerful king, named Tapta, fought with you.

You, your army destroyed by him who had defeated you, died and, because you were subject to cruel meditation*, you became a hell-inhabitant in the sixth hell. Vasantasena entered the fire, grieved by the separation, died, and was born at that time in the same hell. You, having risen from hell, became the son in the house of a poor man in Bharata in Puskaradvipa and she became a daughter of a caste equal to his. The marriage of the two took place when they were grown and, though the pain of poverty was present, you two sported constantly.

One day you two were at home and saw some sadhvis. Getting up with devotion, you presented them with food* and drink zealously. Questioned, the sadhvis said, ‘Our head is Balacandra and there is shelter in the house of Sheth Vasu.’ At the end of the day, you two went there, your minds purified, and were taught dharma* completely by the head-sadhvi, Balacandra. You both adopted lay-dharma at her feet and, after death*, became gods with a life of nine sagaras in Brahmaloka. After falling, you became these two (you are now). You made severe separation of animals in your Bhilla-birth and she approved it. By the maturing of that (karma) you experienced the death of your wives, separation, and the pains of capture, imprisonment, et-cetera. For the maturing of karma is painful.”

Bandhudatta bowed again and said to the Blessed One: “In future where shall we go and how long will our existence be.?” The Master replied: “After death, you will go to Sahasrara. Falling, you will be a cakrin in East Videha and she will be your chief-queen. After enjoying the pleasures of the senses for a long time and after becoming mendicants, both will go to emancipation.” Hearing that, Bandhudatta and Priyadarsana took the vow at that very time under the Master, Sri Parsva.

One day a king, a lord of nine treasures, went to pay homage to Parsva who had stopped in a samavasarana near his city.”By what acts in a former birth did I attain this magnificence?” So questioned by him, the Blessed One, Lord Parsva said:

“In a former birth you were a gardener, AsokaB by name, in a village, Hellura, in the country Maharastra. One day after selling flowers, you started home. Half-way on the road, you entered a layman’s house where the statue of an Arhat was set up. Seeing the Arhat’s statue there, looking for flowers, you put your hand in the basket and found there nine flowers. You put them on the Arhat and acquired great merit.

One day you presented a priyangu-blossomB to the king. You were installed by the king as the head of the guild and, when you died, you became lord of nine lacs of drammas269 in Elapura. After death you became lord of nine crores of money270 in the same place. When you died, you became lord of nine lacs of gold in the city Svamapatha. After death you became lord of nine crores of gold in the same place. After death you became master of nine lacs of jewels in Ratnapura. In course of time you died and became master of fully nine crores of jewels in the same city, Ratnapura. You died and became a king, the son of King Vallabha in Vatika, lord of nine lacs of villages. Then you died and became such a king lord of nine treasures. From this birth you will go to the Anuttara-palace.”

After hearing the Master’s account, the king, very devout, became a mendicant at that time.

This same act is customary for those devoted to sense-objects, (but) without money in the house. If there is anything unusual, hear: In the city Pundravardhana, I am the son, Narayana, of the Brahman Somadeva. I constantly taught the people that heaven was from killing living creatures, et-cetera.

One day I saw some sad-faced men arrested on the suspicion that they were thieves. ‘All these rogues should be killed,’ I said at that time. A muni said, ‘Oh! the wicked ignorance!’ I bowed and asked the muni, ‘hat ignorance?’ and he said: ‘The imputation of non-existent crime, causing great pain to another. These men have fallen into misfortune from the ripening of former karma. Why do you invent a non-existent crime of thievery? Soon you will find the full fruit of acts committed in a former birth. So do not impose a false crime on another.’

Asked by me again about the full fruit of former acts, the muni, who had supernatural knowledge, his mind filled with compassion, said:

Former birth of thief

‘In this same Bharataksetra in the city Garjana, there was a Brahman, Asadha by name, and his wife Racchuka. Now in the fifth birth (before this) you were their son, Candradeva, and you were taught the Vedas by your father. Considering yourself learned, you were much honored by King Virasena. Another mendicant, named Yogatman, intelligent, was there. There was a child-widow, Viramati, the daughter of Sheth Vinita, and she went off with a gardener, Sinhala. Yogatman had been worshipped by her and by chance he went somewhere else on the same day without telling anyone because of freedom from attachment.

“Viramati has gone,” was the gossip among all the people. You reflected, “Surely Yogatman has gone with her.” “Viramati has gone somewhere,” was the talk in the palace and you said definitely, “She has gone with Yogatman.” The king said, “He has given up association with his wife, et-cetera,” and you said, “For that very reason he, a heretic, has taken other men’s wives.” On hearing that, the people became lax in religion and on account of that sin the other mendicants expelled Yogatman.

Having acquired in this way sharp, firmly bound karma,268 after death* you became a goat in the hamlet Kollaka. Having a putrid tongue from the fault of that karma, after death* you became a jackal in a great forest of Kollaka. After the jackal had died from cancer of the tongue, you became the son of Madanalata, a courtesan of the king in Saketa.

One day you, a young man, intoxicated, were restrained by a prince when you were insulting the king’s mother and you insulted him, also, deeply. He cut off your tongue and you, ashamed, fasted and died. Now you became a Brahman. The rest of your actions you know already.’

After hearing that, having disgust with existence which had been produced, I became a mendicant at the feet of Suguru, eager for obedience to a guru. The magic arts of ‘going-through-the air’ and of opening-locks were given to me by the guru as he was dying and I was instructed earnestly: ‘These magic arts must not be invoked in any other calamity except the rescue of a righteous person; and no falsehood must be spoken even in jest. If a falsehood is told through carelessness, you should recite the magic arts one thousand and eight times, standing in water up to the navel, holding the arms erect.’

Devoted to sense-objects I have done the reverse. Yesterday I told a falsehood in front of the habitation in the garden.

Yesterday some young women, after bathing, came to worship the god in the habitation and asked me the reason for taking the vow, I said carelessly the reason was the separation from a dear wife and I did not make the prayer prescribed by the guru, standing in water. At night in order to steal I entered, like a dog, Sheth Sagara’s house whose door happened to be open. As I was leaving after taking the gold, silver, et-cetera, I was caught by the police; and the magic art, ‘going-through-the air,’ did not manifest itself, though recalled.”

The minister asked him again: “Only a box of ornaments has not been found. Were you mistaken about the place?” He said: “The box was taken from the place where it was buried by someone who came and learned about it by chance.”

After hearing that the chief-minister released the ascetic and he remembered the uncle and nephew who had taken the box. He thought: “Surely the box was taken by them in ignorance and they lied because they were terrified. They must be questioned without fear* on their part.” He summoned them and questioned them unafraid. When they had told everything in detail, they were released by the minister conversant with right conduct.

They stayed two days because of emaciation and left on the third day; and they were caught by Candasena’s men who were looking for men. They were both thrown into the midst of prisoners by Kiratas for the sacrifice to the goddess Candasena. Taking Priyadarsana with slave-girls and her son, Candasena approached for the worship of Candasena. Saying, “Merchants’ wives are not able to look at this terrible goddess,” he covered Priyadarsana’s eyes with a cloth. After taking the boy himself, Candasena by a signal of his eye had Bandhudatta brought, the very first one by chance. The village-chief said to Priyadarsana, “After having your son bow to the goddess and having him give her red sandal, have him worship her,”

He himself, completely pitiless, drew his sword from its scabbard, but miserable Priyadarsana thought:

“Alas! this sacrifice with men to the goddess is for my sake. How has this inglorious thing been caused by me! Oh! Oh! I have become a Raksasi.”

Bandhudatta, knowing that death* had come, pure-minded, began to recite namaskaras, virtuous. Hearing his voice, at once Priyadarsana opened her eyes and saw her husband. She said to Candasena, “Brother, you have been faithful to a promise, since this is Bandhudatta, your sister’s husband.” Falling at his feet, Candasena said to Bandhudatta:, “Pardon this crime of ignorance. You are master. Give orders.”

Delighted, Bandhudatta said to Priyadarsana, “What crime is there of this man who has reunited me with you?” Then giving orders to Candasena, Bandhudatta had the men released from prison and said to him, “What is this?” and the Bhilla-king told the story ending in the offering for the fulfillment of his wish.

Bandhu said: “Pooja with living creatures is not fitting. You should worship the goddess with flowers, et-cetera. You should avoid injury, other people’s money and wives, and falsehood. Be a vessel of contentment.” He agreed, “Very well,” and the goddess, being near, said,” Beginning with today, my worship must be made with white lotuses, et-cetera.” Hearing that, many Bhillas became bhadrakas at once.

The son was handed over to Bandhudatta by Priyadarsana. Bandhudatta handed over his son to Dhanadatta and told his wife, “He is my maternal uncle.” She veiled herself and bowed from a distance to her father-in-law. He gave a blessing and said, “A name for the son is fitting today.” Since he had given joy to his relatives by the gift of life, his parents gave him the name Bandhavananda.

After conducting Bandhudatta and his uncle to his house, the Kirata-chief gave them food* and then handed over the loot that he had taken. Candasena, his hands folded respectfully, brought tiger-skins, chauris, elephant-tusks, pearls, fruit, et-cetera to Bandhudatta. Bandhu dismissed the prisoners, like brothers, with suitable gifts and, having helped Dhanadatta to accomplish his purpose, sent him to his own home.

Bandhudatta went to the city Nagapuri with the caravan, his son and Priyadarsana, accompanied by Candasena. His brothers, who came delighted, and the king had him mount an elephant* and enter the city with much honor. Bestowing gifts, Bandhudatta went to his own house and told his whole story to his brothers at the end of a meal.

Again he said to all: “Everything in this existence is worthless except the doctrine of the Jinas. This is my experience.” The people became devoted to the doctrine of the Jinas from Bandhudatta’s speech. Bandhudatta entertained Candasena and dismissed him. Bandhudatta lived there in comfort for twelve years. One day in autumn Srimat Parsva stopped in a samavasarana. Bandhudatta went there with Priyadarsana with great magnificence, bowed to Sri Parsvanatha and listened to a sermon.

Then the Teacher of the World, wandering for the benefit of all the world, went one day to the country Pundra, which was like a tilaka of the earth.

Story of Sagaradatta

Now there was at that time in the city Tamralipti in the eastern territory a merchant’s son, Sagaradatta, knowing the arts, young, intelligent. He was always averse to women from the memory of former births which had taken place and he did not wish to marry any woman, even though beautiful. For he, a Brahman in a former birth, had been abandoned, unconscious, somewhere else by his wife who had given him poison, because she was in love with another man. He had been restored to life by a herd-girl and he became a mendicant. He died and became the merchant’s son, with memory of his former birth, averse to women. The herd-girl, devoted to worldly matters, died in course of time and became the beautiful daughter of a merchant in the same city.

She, won with dignity, was chosen for Sagaradatta by his brothers together with the idea, “His eyes should take pleasure in her.” Yet his mind did not relax even on her. For he considered women to be messengers of Yama, because of his experience in his former birth. The merchant’s daughter thought: “There is some memory of a former birth. He has been mistreated by some courtesan in a former birth.”

After reflecting thus in her mind, at the right time she herself wrote a sloka on a leaf and sent it. He read: “It is not fitting for a man, who has been burned by a milk-pudding, to abandon curds. Are small creatures that originate in a little water present in milk?” After considering carefully the meaning, he wrote and sent a sloka. She read: “A woman takes delight in an undeserving person; a river flows to low ground; the cloud rains on the mountain; Laksmi resorts to a man devoid of merit.” After considering the meaning, in order to enlighten him, she again wrote and sent a sloka. He read: “Where is the fault of the writer? Why the abandonment of her by one so great? Surely the sun does not abandon the devoted twilight.” Pleased by such words, Sagaradatta married her and, delighted, enjoyed pleasures daily.

Then one day Sagaradatta’s father-in-law went with his sons to the town, Patalapatha, to trade. Sheth Sagaradatta also began to do business and sometimes went to another coast with a very large ship. Seven times his ship was wrecked in the ocean and, when he returned, he was laughed at by the people, “He is without merit.” His money lost, he did not abandon effort.

One day in his roaming he saw a boy drawing water from a little well. Seven times the water did not come, but it came the eighth time. After seeing that, he thought, “Men’s efforts are fruitful. Even Fate fears those, for whom it has made obstacles*, whose energy is unhindered by obstacles and who do not abandon an undertaking, and it (Fate) is broken.”

With this thought, he tied an omen-knot, set out for Sinhala by boat, and arrived at Ratnadvipa because of the wind. There he sold his merchandise, bought collections of jewels, filled the boat with them and started to his own city. The sailors, coveting the jewels, threw him in the ocean at night. By chance he reached a plank from a boat wrecked before and he swam out. He reached Patalapatha on the coast, where his father-in-law saw him and took him to his house.

After bathing, eating, and resting, Sagara told the affair of the sailors from the beginning and his father-in-law said: “You stay here. The sailors will not go to Tamralipti from fear* of your relatives, but, stupid, will come here.” Sagara agreed and his father-in-law told the story to the king. For that is the rule of the far-seeing.

One day the ship came to that shore and was recognized by the king’s agents from signs described by Sagara. The king’s men asked all the wretched sailors:266” Who is the owner of the cargo? What is the cargo? And how much is here? “They, terrified and answering one way and another, were observed and the agents quickly summoned Sagaradatta. When they saw Sagara, terrified, they bowed and said: “At that time we, candalas in acts, did a wicked thing, lord. Yet you were saved by your merit, but we have been brought to the edge of capital punishment on your account. Do what is fitting to be done by the master.” Compassionate Sagara had them released by the king’s men, gave them some food* for the journey, and dismissed them, pure in mind. He, noble-minded, was highly honored by the king, saying, “He has merit,” and he acquired much money from the merchandise on the boat.

He gave gifts and, seeking dharma*, asked the teachers of dharma:267” I wish to make the god of gods in jewels. Say who he is.” There was no agreement among them who had no trace of the truth about god. Then a learned man said: “Do not ask stupid men like me. After practicing penance, and investing a jewel with divinity, concentrate your thoughts. The gods will tell you who is the supreme god.”

Sagara did so and at the end of a three-day fast, a deity showed him a purifying statue of a Tirthakara. The deity said to him, “Sir, this is the Supreme God, whose true nature the munis no others know.” With these words, the deity went away. Sagara, delighted, showed the sadhus the golden statue of the Arhat. The sadhus taught him the dharma* taught by the Arhats and he became a layman.

One day he asked the sadhus: “Of which Arhat is this the image? By what procedure must I install it? Now do your Reverences tell me.” The sadhus said: “Sri Parsva is now stopped in the district Pundravardhana. Go and ask him.” Sagara went at once, bowed to Sri Parsva and asked him about the procedure suitable for the jeweled statue in all respects. The Master explained to him with reference to his own samavasarana all the supernatural powers of the Arhats, the worship of the Jinas, and the installation (of the statue). He had it installed in accordance with the procedure prescribed by the Jina, thinking, “It is the statue of a Tirthakrt.” The next day he became a mendicant in the presence of the Master. Then the Blessed One with his retinue, attended by gods and asuras, endowed with all the supernatural powers, went elsewhere.

Now in the city Nagapuri, there was a king, Suratejas, the chief of the glorious, like the Indra of the serpents in the city of the Nagas. There was a rich man, Dhanapati, friend of the king, and Dhanapati’s wife Sundari, fair in conduct. They had a son, Bandhudatta, who had his grandfather’s name, well-bred and virtuous, and he reached youth. Manabhanga, by whom his enemies minds were broken, was king in the city Kausambi in the country Vatsa. There was a rich man, Jinadatta, devoted to the religion of the Jinas, who had a wife Vasumati and a daughter, Priyadarsana. She had a friend, the daughter of the Vidyadhara, Angada, named Mrgankalekha, devoted to the Jinas’ doctrine. The two friends passed the days with worship of the gods, service to the guru, study of dharma, et-cetera.